Uncategorized

Tracing Human Migration in Melanesia

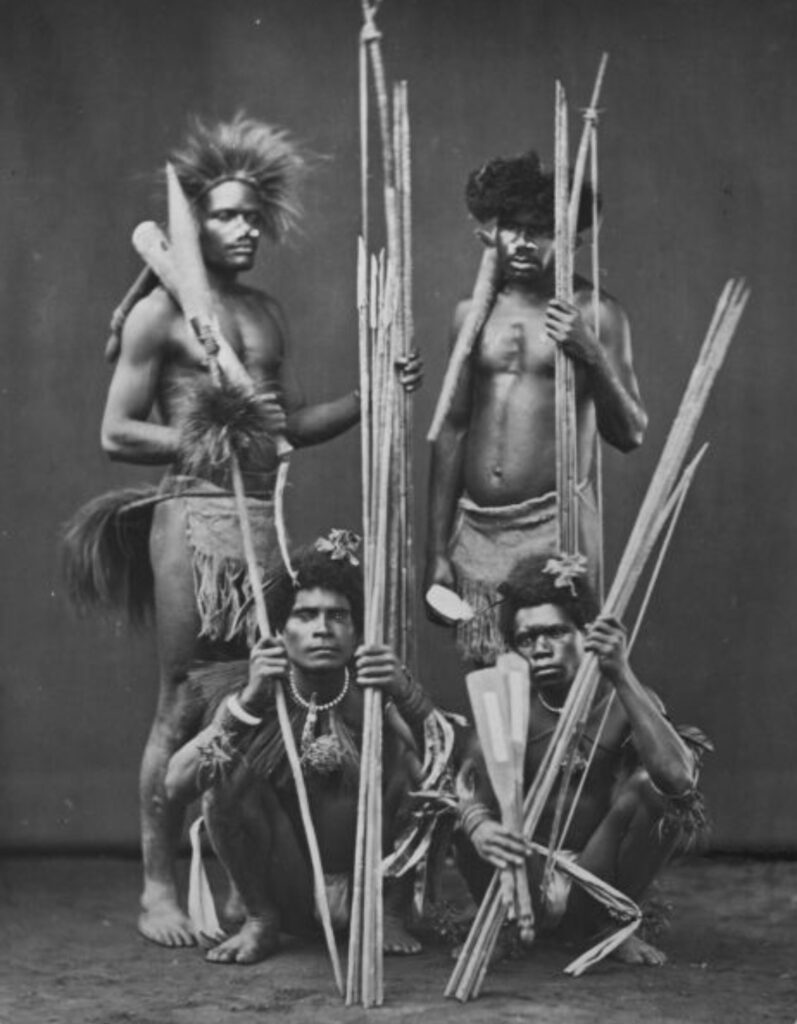

Melanesia is a region of remarkable diversity. The territory of Melanesia includes Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, Fiji, and New Caledonia. The term Melanesia was first introduced by Dumont D’Urville in 1832. Dumont D’Urville classified the Pacific into three parts: Polynesia, Melanesia, and Micronesia. The word ‘Melanesia’ is derived from the Greek melas which means black and nesoi which means islands. Melanesia was initially classified as a distinct race, historically referred to as the Melanesian race.

In The Malay Archipelago, Alfred Russel Wallace categorized the peoples of Nusantara into two racial groups: Malay and Papuan. The Malay race inhabits most of the western regions of Nusantara, while the Papuan race inhabits Papua Island and the surrounding islands. In some areas, ethnic groups were identified as transitional between the two racial categories. However, from a biological perspective, there is only one modern human race: Homo sapiens. Consequently, racial terminology is no longer used in contemporary biology. Melanesian populations are instead understood as part of the Australomelanesid grouping, and Australomelanesid populations, along with all other human groups worldwide, are classified within the single species Homo sapiens.

When Homo sapiens emerged, Homo erectus, which had inhabited Java for a much longer period, appears to have become extinct. Some scholars have linked the extinction of Homo erectus to an inability to adapt to environmental changes. Based on the Out of Africa theory, Homo sapiens left Africa and spread to various directions in 100.000 BP. Under this model, Homo sapiens is thought to have arrived in Nusantara between 126,000 and 80,000 BP. During the Upper Pleistocene, populations continued migrating southward toward Australia. Fluctuations in sea levels during this period caused land areas to shrink, reducing food resources and prompting further human migration.

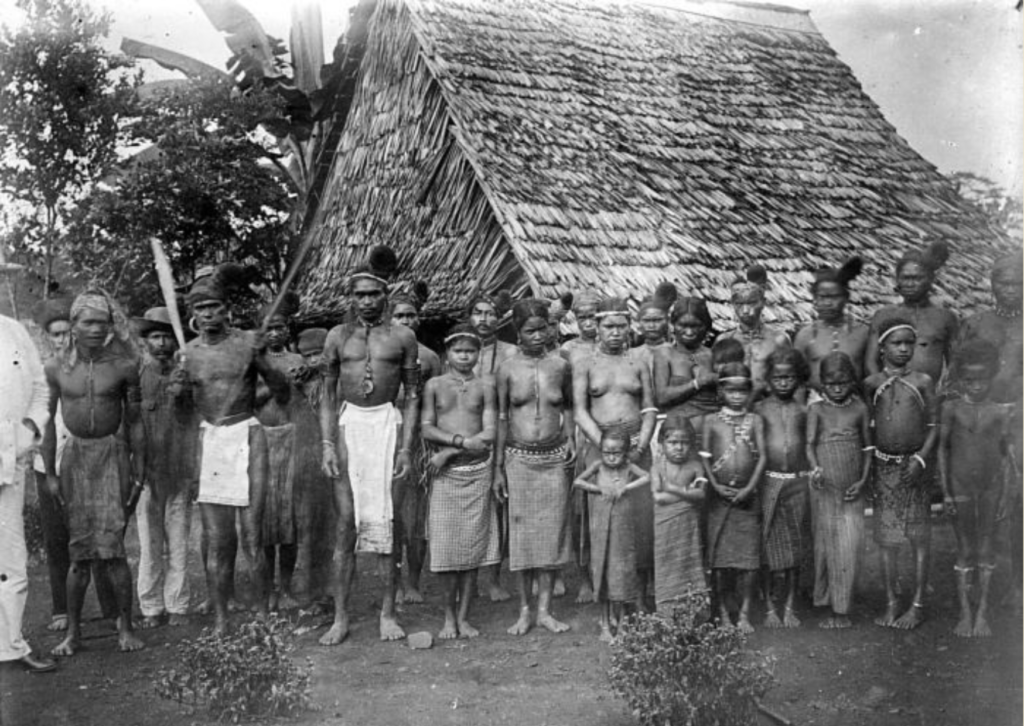

Before the Ice Age, Sumatra, Java, and Borneo were part of the Asian continent, while Papua was a separate landmass connected to Australia. The Ice Age set those islands apart. By that time, Homo sapiens had entered Nusantara and occupied areas that had previously been uninhabited. They lived in caves and had already begun using stone tools. Unlike Homo erectus who wander, Homo sapiens began to inhabit caves, hunting, and gathering. In Southeast Asia, Melanesia, and Australia, the descendants of Homo sapiens developed physical characteristics that distinguish them from other human populations worldwide. Bioanthropologists have classified these populations as Australomelanesid, a subspecies of Homo sapiens.

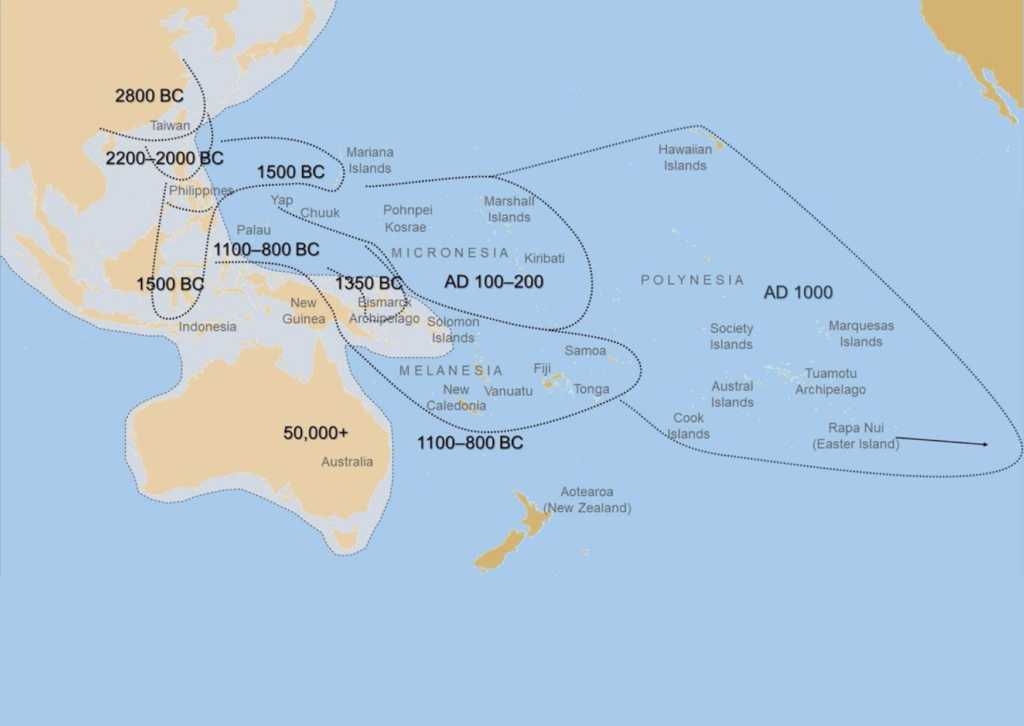

The population of Melanesia is the result of multiple migration flows from Mainland Asia into the islands of the Southwest Pacific. Archaeological evidence indicates that early human populations reached the Melanesian islands, including Fiji, before continuing their maritime journeys eastward. These seafaring groups eventually reached Easter Island, the easternmost point of Polynesia, where settlement began around 300 AD. The southernmost extent of this expansion was New Zealand, which was settled around 800 AD. In bioanthropological terms, Melanesoid is the taxonomy of the indigenous population that inhabits Melanesia territory. The inhabitant of Polynesia occurred after the migration of Melanesian thus the population of Polynesia came from the integration of Southeast Asian and Taiwanese with Melanesian.

Around 4.000-3.000 BCE, the Austronesian and Mongoloid elements migrated into the region via two main routes. The first was the western route, which moved from the Malay Peninsula into Sumatra, Java, and Borneo. These newcomers spoke Austroasiatic languages–the language spoken in Mainland Asia, such as Mon-Khmer and Munda. The cultural products that marked this western migration route include cord-marked pottery or cord-impressed pottery, pickaxe, belincung stone axe and simple plank boat. The second route was the eastern route which came from Taiwan, the Philippines, Sulawesi, and Borneo. These newcomers spoke Austronesian language and their main cultural markers were simple outrigger axe, red-slipped pottery, shouldered adze, stepped adze, oval axe.

The Austronesian immigrants brought neolithic and megalithic practice, and were characterized by settling and domestication of animals and plants.From Sulawesi, Austronesian-speaking populations spread across the Indonesian archipelago and beyond, reaching the eastern Pacific, Malaysia, Vietnam, and even Madagascar. This spread influenced language use in the region. Austroasiatic languages, which once dominated western Indonesia, were gradually replaced as populations adopted Austronesian languages. The arrival of Austronesian speakers also led Australomelanesid populations, the ancestors of Melanesians, to move from western Indonesia to the eastern regions of the archipelago.

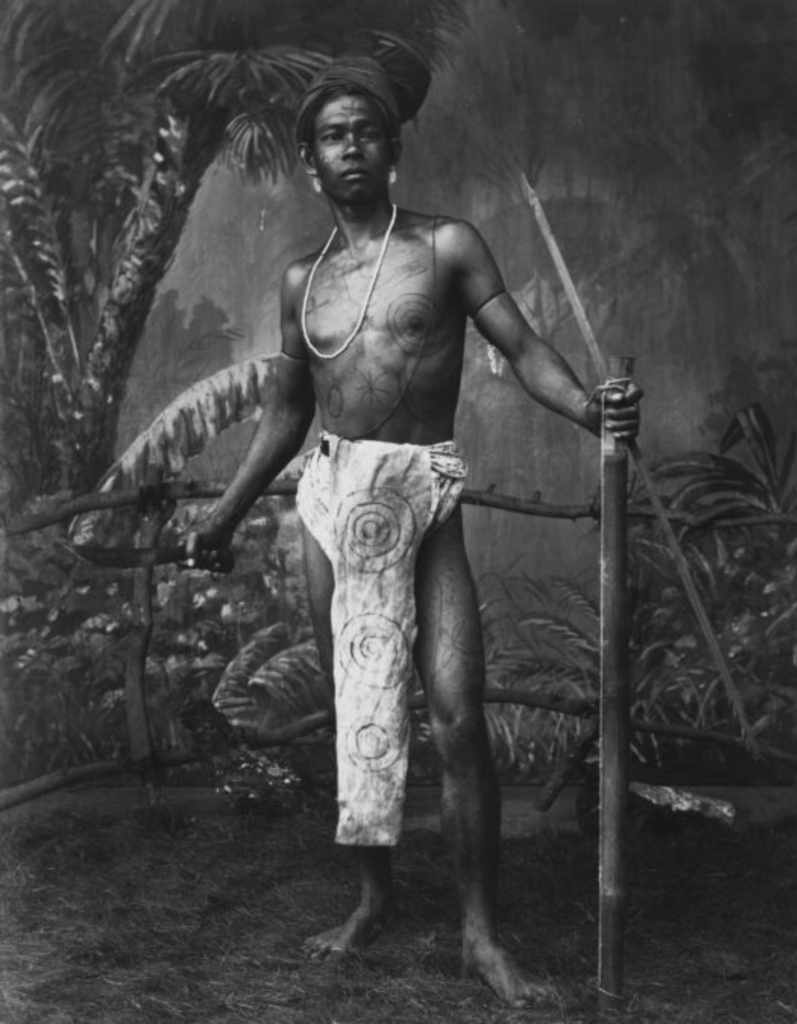

Interaction between populations historically described as Mongoloid and Australomelanesid led to genetic and cultural mixing. Communities in Maluku and East Nusa Tenggara live within an intensive contact zone shaped by this interaction, resulting in mixed physical and cultural characteristics. Although influences associated with Mongoloid ancestry are present, Melanesian traits remain dominant. More pronounced Melanesian characteristics are found among inland populations of Papua. The diversity of their physical characters we see today can be explained from the history of hybridization, isolation, and their response towards different environmental situations.

The majority of the Indonesian population is genetically mixed, with ancestry from two or more sources. Austronesian genetic ancestry is more dominant in western Indonesia, while Papuan genetic ancestry is higher in the eastern regions. Although present at lower levels, Papuan genetic ancestry can be found in many parts of western Indonesia. Likewise, Austronesian genetic ancestry is also found within Melanesian regions.

The Austronesian speaker in Melanesia generally only spread in the northern coastal area. They are estimated to have entered Melanesian territory around 3,000 years ago. Evidence of their presence can be found at Neolithic sites in Raja Ampat, Kepala Burung, Manokwari, Biak, Yapen, and Sentani. In the southeastern coastal areas, evidence of their distribution is also found at cave painting sites in Kaimana and Berau Bay. Austronesian languages spoken in the Pacific show that the easternmost extent of Austronesian distribution reaches the eastern region of Jayapura. Interaction between Melanesian populations and Austronesian-speaking groups gave rise to what has been described as the Austro-Melanesoid population.

Indigenous highland communities in Papua tend to have darker skin and curly hair, similar to Aboriginal Australians. Some scholars have classified these populations as belonging to the Papuid subrace, while others consider them Melanesian, noting certain distinctions between the two. Archaeological sites at Anyer, East Java, Gilimanuk, and Sumba indicate that, at least since the protohistoric period, intermarriage between different population groups occurred in several areas. Such intermarriage appears to have been more intensive in Maluku, as the region lay along major migration routes toward the Pacific.

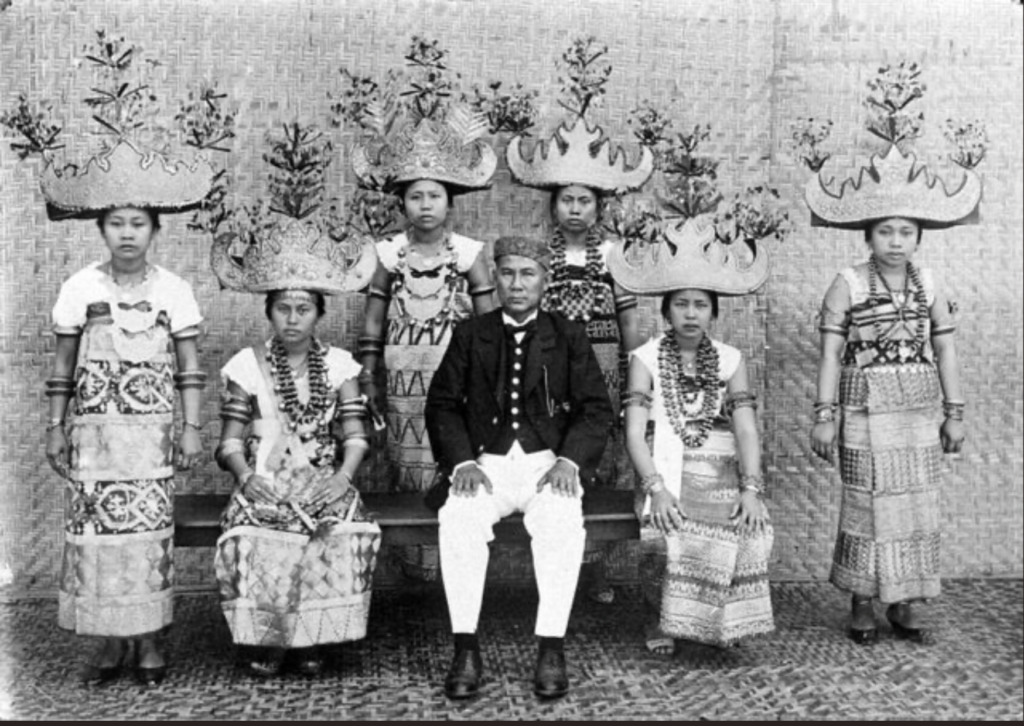

The Austronesian enriched the Melanesian culture by promoting the culture that fit in the Pacific environments. This culture is referred to as Lapita culture which is characterized by open villages with square stilt-house, food-gathering, animal domestication, betel nut consumption, and pottery and jewelry production. However, rice cultivation only reached the western islands of Micronesia in the Pacific and not spreading to Melanesia. The oval stone axe became the tools that simplified everyday lives then developed as social status symbol, dowry, even customary debts.

Melanesia has one of the highest levels of linguistic diversity in the world. In Indonesia, of more than 700 local languages, around 400 are spoken in Papua. Papuan languages are generally divided into two groups: Austronesian and non-Austronesian. The non-Austronesian languages form a highly diverse set of language families that are not closely related to one another. These languages are found across western Melanesia, Papua New Guinea, New Britain, and the western Solomon Islands. They are believed to have been introduced by early settlers who migrated from mainland Asia and spread eastward across Melanesia. Meanwhile, the native Austronesian language developed into proto-Indonesian, proto-Melansian, and proto-Polynesian language.

The migration route proves that the native Indonesians today are part of two or more genetics. No ethnic group in Indonesia can be considered genetically “pure,” as each has been shaped by a long and complex history of human migration. This integration has enriched Indonesia with the diversity we see today.

Bibliography

Abdullah, T., & PaEni, M. (Ed). (2015). Diaspora Melanesia di Nusantara. Jakarta: Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan.

Capell, A. (I962). Oceanic linguistics today. Current Anthropology, 3(4).

Lawson, S. (2013). ‘Melanesia’. The journal of Pacific history, 48(1), 1-22. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00223344.2012.760839

Leclerc, M., & Flexner, J. (Ed). (2019). Archaeologies of Island Melanesia: Current approaches to landscapes, exchange and practice. Australian National University Press.

Murdock, G. P. (I964). Genetic classification of the Austronesian languages: A key to Oceanic culture history. Ethnology, 3(2).

Shutler, M. E., & Shutler, R. (1967). Origins of the Melanesians. Archaeology & Physical Anthropology in Oceania, 2(2), 91-99. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40386005

Simanjuntak, T. (2005). Indonesia-Southeast Asia: Climates, settlements, and cultures in Late Pleistocene. Human Palaeontology and Prehistory, 5(1), 371-379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crpv.2005.10.005

Storm, P. (2001). The evolution of humans in Australasia from an environmental perspective. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 171(3), 363–383. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0031-0182(01)00254-1