Uncategorized

Damai Tumbang Anoi: The End of Dayak Tribal Wars

Borneo is one of the most diverse islands in Indonesia, both in its biodiversity and its cultural communities. Borneo is home to the Dayak tribe which has 268 sub-ethnic groups and are categorized into six clusters: Punan, Klemantan, Apokayan, Iban, Murut, and Ot Danum. Despite their differences, the Dayak people live in harmony and peace. Long before this, the Dayak tribes often fought among themselves, even for trivial reasons. This diversity made the Dayak people vulnerable to conflict.

During the time when headhunting was practiced by the Dayak, escalating conflicts often culminated in headhunting. The group that managed to decapitate their enemy’s head was declared the victor of the war. However, these conflicts often led to significant loss of life without producing a definitive winner. Ultimately, the wars proved futile, as the Dayak people lacked a unified legal system to guide all the tribes across Borneo. When conflicts escalated, war became the solution. Therefore, the Dayak people eventually gathered in the village of Tumbang Anoi, Central Borneo, to discuss and establish customary laws that would guide the Dayak people and prevent them from resorting to war to settle conflicts. This event is known as the “Damai Tumbang Anoi” (Tumbang Anoi Peace).

Damai Tumbang Anoi became a pivotal event that enabled the Dayak people to live in harmony. However, this agreement was not achieved without a conflict. The conflict that led to the creation of Damai Tumbang Anoi occurred between the Dayak Ngaju tribe, who lived in Kahayan, Central Borneo, and the Dayak Kenyah tribe, who inhabited Mahakam, East Borneo. The root of the dispute was the competition over a place to harvest Nyatu sap. Nyatu sap was an essential part of daily life for the Dayak Ngaju people in Kahayan. They harvested the sap from the Puruy Ayau and Puruk Sandah mountains, located along the border of Central and East Borneo.

The misunderstanding between these two tribes led to a headhunting war, known as “Kayau 100,” which occurred in Tumbang Tuan, Central Borneo. The first attack was carried out by the Dayak Kenyah tribe, led by war chiefs Sangiang Hadurut and Tingang Koai. The targeted areas for the headhunting included Kurun Tampang, Sei Miri, Sei Hamputung, Pajangei, Sei Beringei, and Sei Rungan.

The Dayak Ngaju tribe from Kahayan took revenge, led by four war chiefs: Undeng (the leader), Teweng, Batoe, and Beneng. These war chiefs were chosen by the Kahayan people through the Menajah Antang ritual. In this ritual, spirits were summoned and appeared in the form of an eagle. This ritual is a hereditary tradition that can only be performed by those who understand the Dayak’s ancestral languages, such as Sangiang and Nahu, and practice the Kaharingan religion. The Menajah Antang ritual was performed by Basir, Pisur, or Tukang Tawur, individuals who can communicate with the spirit world.

The Dayak Ngaju from Kahayan sent a headhunter emissary to the Dayak Kenyah with a decorated bamboo pole (tutuk bakaka) and a mandau (Dayak sword), signaling that a war would take place. The message stated that the Dayak Ngaju from Kahayan were ready to face the Dayak Kenyah in an open war at Tumbang Tuan. In vengeance, the Dayak Ngaju sent 200 people and eight regeh (canoes) made from tree bark.

In the first battle, Udeng and his forces were defeated and retreated to the village of Long Bagun. In the second battle, Udeng’s men were killed, but the war chiefs survived. Meanwhile, from the Dayak Kenyah side, Sangiang Hadurut and his forces were killed in the open battle. Tingang Koai committed suicide because he felt ashamed to be captured by the enemy. Neither side emerged as a clear winner.

The headhunting war eventually reached the Dutch East Indies government, based in Nanga Pinuh, West Borneo. The Dutch authorities sought a solution to end the conflict by halting the headhunting raids and establishing a customary law for all Dayak people across Borneo. With this customary law, the Dayak people in Borneo would adhere to a single guiding principle for resolving issues that might arise.

Two prominent Dayak figures, Damang Batoe from Tumbang Anoi and Tamanggung Tendan from Puruk Island (now Tewah District), initiated a peace meeting between all Dayak tribal leaders. The Dayak leaders were brought together at Damang Batoe’s traditional Betang house. Unfortunately, this historic house now only stands as a memory, with only the pillars remaining. Tumbang Anoi, a village in the Damang Batu sub-district of Gunung Mas, Central Borneo, became the location for this grand meeting, where all Dayak leaders gathered together to end the headhunting tradition.

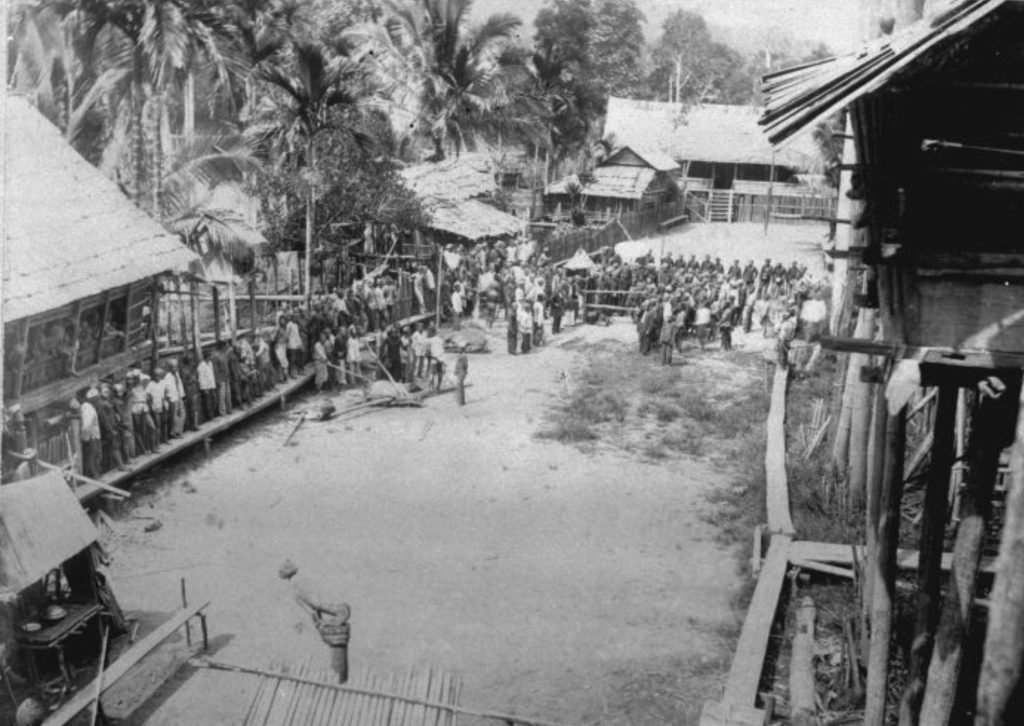

This grand meeting required extensive preparation. Tumbang Anoi was set to host over a thousand guests for the meeting. The people of Tumbang Anoi spent three years preparing for the event, clearing fields on nearby hills to plant rice and cassava. They also raised hundreds of livestock, including buffalo, cattle, pigs, and chickens, to feed the participants after the harvest season.

According to historical records, Damai Tumbang Anoi took place from May 22 to July 24, 1894. However, the people of Tumbang Anoi believe the meeting occurred in 1883, almost coinciding with the eruption of Mount Krakatoa. The meeting was attended by more than 1,000 people and lasted for three months. In addition to the Dayak people, representatives from the Banjar Kayu Tangi Kingdom, the Sultanate of West Borneo, and the Dutch East Indies government were also present at the meeting.

Through this meeting, an agreement was reached to stop inter-tribal feuds, headhunting, and conflicts with the Dutch East Indies government. The meeting also established a customary law for all Dayak tribes across Borneo. Since then, the Dayak people have been united by the same customary law that helps each tribe process legal matters in the same way. As a result, headhunting between the tribes no longer occurs when conflicts arise. Damai Tumbang Anoi became a historic moment that shaped the harmony of the Dayak people, a harmony that continues to be felt today.

Source: Adi/Nawri, based on discussions with the elders of the Kenyah Dayak tribe in Samarinda (East Borneo) and Palangkaraya (Central Borneo)