Uncategorized

Nusantara’s Spice Route: Tracing the History of Black Gold Hunting

Spices play a crucial role in Indonesian cuisine. Indonesia’s abundant spices, influenced by its geographical factors, contribute to the robust flavors found in Indonesian cuisine, widely cherished by many. Historically, spices symbolized wealth and were even dubbed “black gold” due to their high value. Who would’ve thought that the spices we commonly consume daily once played a significant role in changing human civilization?

The history of European exploration was fueled by the quest for spices, triggered by the fall of Constantinople to the Turks, disrupting the traditional trade route from Asia to Europe. Consequently, the price of spices skyrocketed, rendering them increasingly scarce and expensive. Despite this, Europeans had already developed a taste for spices and were determined to secure access to them. Thus, they embarked on ambitious explorations in search of the coveted Spice Islands. In 1498, Portuguese explorer Vasco de Gama accomplished the first sea voyage from Europe to India. Alongside de Gama, numerous other European sailors embarked on expeditions to discover the Nusantara archipelago.

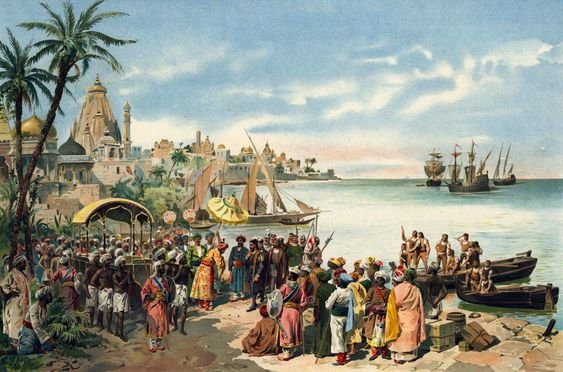

The Nusantara archipelago has long been renowned as a major spice producer. Even before the era of European exploration, the spice route was established as a vital trade route connecting the Eastern and Western worlds, with spices as its primary commodity. This maritime route not only facilitated trade but also fostered a maritime culture that disseminated spices to every corner of the globe. Following the spice hunt, the spice route thrived, eventually surpassing the prominence of the Silk Road.

Before the arrival of the Portuguese to the Nusantara archipelago, Malacca served as a trading hub that brought together merchants from India, Gujarat, Bengal, Arabia, China, and surrounding regions. At that time, Malacca was the main port that controlled the spice trade in the Indian Ocean. Its strategic location made this route bustling with international traders. Malacca was also surrounded by regions abundant in natural resources. In 1511, Alfonso de Albuquerque led the Portuguese to seize Malacca and spread Christianity, causing the predominantly Muslim traders to seek other ports to trade.

The fall of Malacca to the Portuguese was good news for the Sultanate of Aceh Darussalam. Muslim traders eventually docked at ports along the west coast of Sumatra and found Aceh as an alternative. The arrival of traders from various regions in Aceh became a route for Islamization along the west coast of Sumatra. Aceh emerged as the central hub of the spice route on the island of Sumatra during the 16th century.

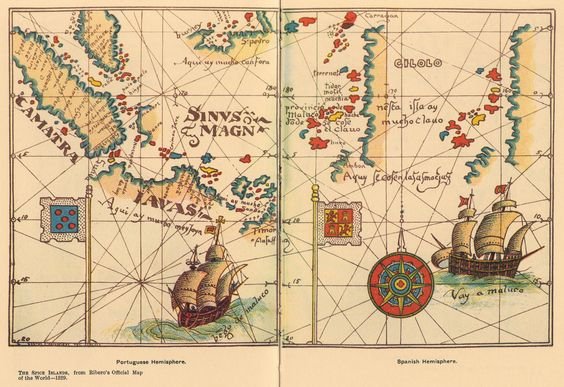

In addition to dominating Malacca, the Portuguese also successfully explored the Maluku Islands, renowned as the Spice Islands and fiercely contested by numerous nations. The Portuguese arrival coincided with a conflict between the Sultanates of Ternate and Tidore, both vying for control over the spice trade center in Maluku through trade alliances known as Uli Lima (Ternate) and Uli Siwa (Tidore). Subsequently, the Spanish followed the Portuguese to assert dominance over the Spice Islands, each striving to gain legitimacy from local kingdoms. Ultimately, Maluku was divided, with the Portuguese aligning with Ternate and the Spanish with Tidore. However, in 1663, the Spanish ultimately withdrew from Maluku to safeguard Manila from Chinese pirate attacks.

Spices, being high-value commodities, prompted European traders to vie for control and monopolize the spice trade. This fierce competition often escalated into wars and genocides. Eventually, the Dutch managed to discover the Maluku Islands, which were initially under Portuguese control. With the support of Ternate, Steven van der Haghen successfully captured Ambon, expelling the Portuguese from the Maluku Islands. In addition to conflicts with the Portuguese, the Dutch also clashed with British trading companies in the 17th century over control of Banda Neira. This conflict is famously known as the Nutmeg War or Perang Pala.

Nutmeg was coveted by many European and Asian trading companies due to its high market value. However, the people of Banda Neira had not adopted the trading patterns of the European nations. The people of Banda sold their spices through barter. Chinese or local traders could buy spices and exchange them for clothing and food, which were essential needs for the people of Banda. Sago was the main commodity needed by the people of Banda. In contrast, European nations exchanged spices for money.Banda heavily depended on food supplies from outside their region due to their reluctance to reduce nutmeg plantation areas in favor of other agricultural crops. European traders, unable to implement conventional trade methods, opted instead to monopolize the nutmeg trade in Banda Neira.

The people of Banda fell victim to genocide in 1621, orchestrated by JP Coen, a general of the VOC, resulting in the massacre of 44 Kaya individuals—Kaya being traditional leaders in the community. This horrific event decimated the population of Banda Neira, leaving only one-third of its inhabitants alive. Meanwhile, the VOC required laborers to oversee nutmeg plantations in Banda Neira and thus brought individuals from various parts of the Nusantara to serve as plantation slaves. Consequently, Banda Neira evolved into a multicultural area as numerous immigrant communities settled there since the VOC era.

The significance of spices began to wane in the nineteenth century, as their role as a leading export commodity in the global market diminished due to competition from emerging commodities. Following the decline of the VOC, Dutch interests in Indonesia shifted from trade to colonialism. Consequently, the Dutch established plantations for coffee, sugar, rubber, and palm oil to cater to the demands of these new commodities in the market. This transition introduced Indonesia to non-native plant species, shaping its agricultural landscape.

While the spice route may be relegated to history, its impact on global affairs continues to resonate. The spice trade transformed Indonesia into a vibrant global hub, fostering cultural exchange and assimilation between diverse communities. Additionally, the spice route facilitated the spread of religion throughout the Nusantara, with Bahasa Melayu emerging as the lingua franca among traders. Although spices were the primary trading commodities, exchanges extended beyond material goods to encompass concepts and knowledge. The enduring effects of these exchanges persist to this day, even catalyzing transformative changes within civilizations.

Bibliography

Anuraga, J. (2021). Jalur rempah Banda, antara perdagangan, penaklukan dan percampuran: Dinamika masyarakat Banda Neira dilihat dari sosio-historis ekonomi rempah. Jurnal Masyarakat dan Budaya, 23 (3). DOI: 10.14203/jmb.v23i3.1483

Mu’aqaffi, G. (2021). The legacy of spice route: the role of Panglima Loat in maritime security in the modern Aceh. Jurnal Masyarakat dan Budaya, 23 (3). DOI: 10.14203/jmb.v23i3.1429

Nawiyanto., Handayani, S., & Salindri, D. (2023). Spices in Indonesia history and its revival. Global Journal of Archaeology & Anthropology, 13 (1). DOI: 10.19080/GJAA.2023.13.555855

Sudarman., Hidayat, A., Taufiqurrahman., & Hidayaturrahman, M. (2019). Spice route and Islamization on the west coast of Sumatra in 17th-18th century. Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, 302. DOI: 10.2991/icclas-18.2019.13

Veen, E. (2001). VOC strategies in the far east (1605-1640). Bulletin of Portuguese – Japanese Studies, 3, 85-105.