Uncategorized

The Aceh War: The Longest Resistance Against Dutch Colonial Rule

The Aceh War was the longest war in Nusantara, resulting in hundreds to thousands casualties from both sides. It lasted for 31 years, from 1873 to 1904, and is compared to the 80 Years War (1568-1648) in the Netherlands. The war is known as the “Aceh War,” while the Acehnese people refer to it as the “Perang Beulanda” (Dutch War), since the Dutch initiated the aggression against Aceh. Meanwhile, the conflict between the two sides had been ongoing since the VOC era, when the Dutch East India Company controlled Nusantara from 1602 to 1799.

When Malacca fell into the hands of the Portuguese in 1511, the Sultanate of Aceh grew and reached its peak under the reign of Sultan Iskandar Muda (1607-1636). The port of Aceh became a major economic power in the Indian Ocean, with pepper as its main commodity. The first contact between the Dutch and Aceh occurred on June 21, 1599, when Dutch trading ships under the leadership of Cornelis de Houtman arrived at the port of Aceh. Initially, the Dutch ships were warmly welcomed by the Sultan of Aceh. However, Portuguese traders were unhappy with the arrival of the Dutch. They began to incite the Sultan of Aceh, leading to growing tensions between Aceh and the Netherlands.

The first attack was made by the Acehnese, who attacked the Dutch ships. As a result, Cornelis de Houtman was killed, while his brother, Frederick de Houtman, was captured by the Acehnese army. From that point, the relationship between the Dutch and Aceh became increasingly strained. The Sultan decided to capture every Dutch trading ship that entered Aceh.

In 1602, Dutch traders under the leadership of Gerard de Roy and Laurens Bicker arrived in Aceh to establish a friendship with the Sultanate of Aceh. They managed to win the Sultan’s favor, and relations between the two improved. The Dutch were allowed to trade freely in Aceh. However, when the throne passed to Sultan Iskandar Muda, he canceled the peace agreement with the Dutch, forcing them to close their trading office in Aceh. The beginning of the rift between the two sides came with the signing of the Pidie Treaty (1819) between Aceh and Britain. One of its clauses was that the Sultan of Aceh would not allow Europeans to settle in Aceh and would not establish relations with European countries without the knowledge of the British government.

At the start of Dutch colonialism in the Archipelago, the Sultanate of Aceh had not yet become a Dutch colony. According to the 1824 London Treaty, Britain controlled the northern part of the Strait of Malacca (now Malaysia), and the Netherlands controlled the southern part of the Strait of Malacca (now Indonesia). The Sultanate of Aceh remained neutral between the two countries but was still under British protection. At that time, Aceh remained a sovereign independent state at the entrance to the Strait of Malacca. However, with the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, the Dutch became increasingly determined to conquer Aceh. Aceh’s strategic position made the Dutch fearful that it might fall into the hands of other Western powers. Additionally, the Sultanate of Aceh was the main obstacle to Dutch territorial expansion in Sumatra.

On November 2, 1871, the Dutch violated the London Treaty and incorporated the Sultanate of Aceh into their colonial territory. The Dutch sent a letter requesting that Aceh recognize Dutch sovereignty. However, this request was firmly rejected by the Sultan of Aceh, leading to open war. On April 1, 1873, the Dutch East Indies government commissioner for Aceh, Nieuwenhijzen, declared Oorlogsverklaring (Declaration of War), dated March 26, 1873. The colonial war to establish Pax-Neerlandica in the northwestern part of the Indonesian archipelago officially began.

In fighting against Aceh, the Dutch believed that Aceh was a weak opponent, and their military equipment was not as advanced as the Dutch’s. However, the Dutch failed to understand the religious, cultural, and social aspects of the Acehnese people, which strengthened their resistance. For the Acehnese, if anything threatened the survival of Islam and their homeland, they would face it with great willpower. In this context, they only knew martyrdom or victory. Social and religious strength was the most decisive factor in driving the Acehnese people’s resistance against the Dutch.

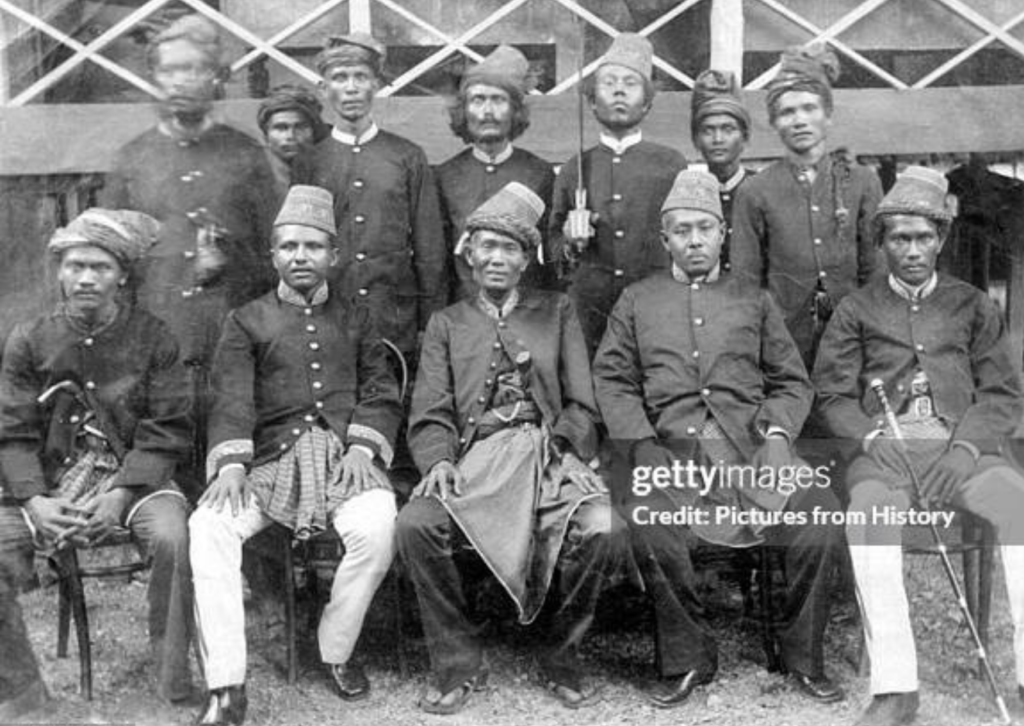

All layers of Acehnese society, from the Sultan, uleebalang (nobles), ulama (religious scholars), to ordinary people, participated in this struggle. Not only men, women also had roles in this war. The first aggression launched on April 5, 1873, ended in complete failure. The Dutch army could not cope with the resistance of the Acehnese people. The second aggression was launched on December 9, 1873, led by Lieutenant General J. van Swieten. The Dutch succeeded in destroying the Baiturrahman Grand Mosque on January 16, 1874, and occupied the Aceh Palace on January 24, 1874. With the success of occupying the palace, the Dutch believed that Aceh had been conquered. Van Swieten declared that Aceh was now Dutch territory.

In reality, the Dutch declaration was meaningless because the leaders of Aceh appointed Tuanku Muhammad Daud Syah as the new Sultan. Since Tuanku Muhammad Daud Syah was still underage, Tuanku Hasyim Banta Muda was appointed as the regent. The Acehnese government was moved to Indrapuri, about 25 km southeast of the former capital. This relocation aimed to facilitate the mobilization of the people to fight against the Dutch. Since then, Aceh had two centers of government: the Aceh Sultanate in Indrapuri and the Dutch colonial government in Kutaraja (former capital of Banda Aceh).

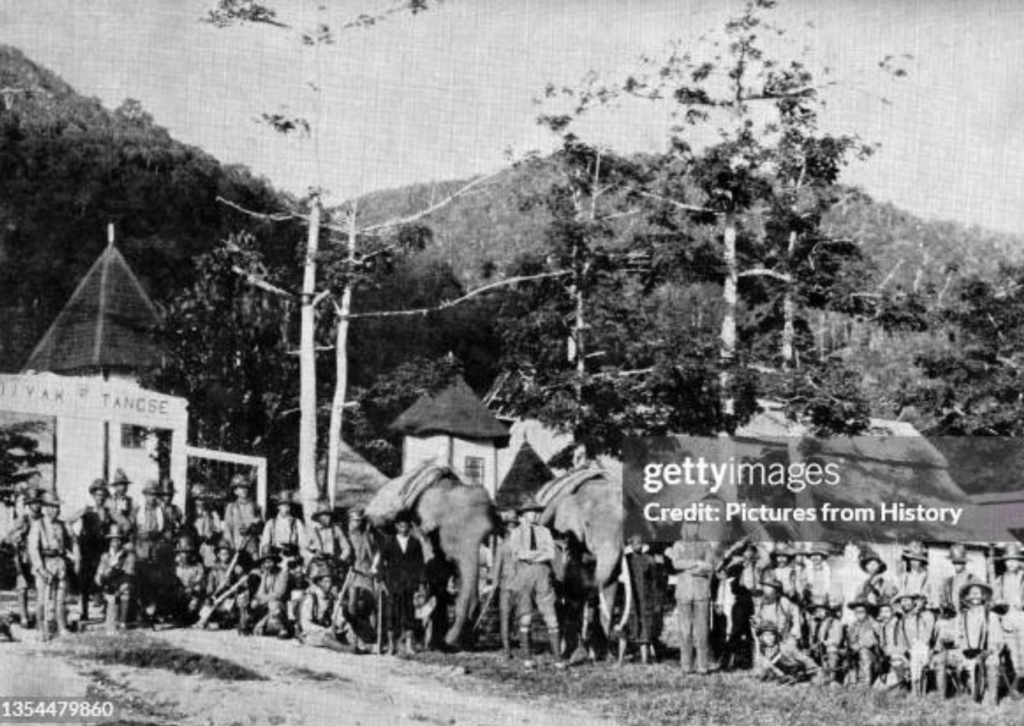

The Dutch then sought to conquer the uleebalang territories outside of Aceh Besar (Great Aceh) because they recognized the importance of these areas as sources of resistance to the Dutch. The Dutch succeeded in conquering Pidie, North Aceh, East Aceh, West Aceh, and South Aceh, forcing these regions to sign treaties with the Dutch. However, these regions remained defiant toward the Dutch, rendering the treaties ineffective. The Dutch found themselves at a loss to make Aceh obey them.

After Tuanku Muhammad Daud Syah came of age, he was crowned the 32nd Sultan of Aceh. Since this, Aceh’s power grew stronger. In December 1877, Acehnese military leaders such as Tuanku Hasyim, Panglima Polim, and Chiek Di Tiro called for an “Ikrar Perang Sabil” (Pledge of Jihad) to fight in the path of Allah against the Dutch infidels. This call to jihad was also presented in the form of a hikayat (folklore). During the war against the Dutch, the Hikayat Perang Sabil was often read to the people before going to battle. The hikayat also encouraged fighting in the way of jihad, promising rewards and happiness in the afterlife. In addition, there was the desire to achieve martyrdom. With this pledge, since 1899, the Dutch had no choice but to launch large-scale attacks on Aceh. The ten years from 1899 to 1909 became a bloody decade in Aceh, taking 21,865 lives (about 4% of Aceh’s population).

The Acehnese resistance made the Dutch powerless. The Dutch East Indies government lacked the funds for military operations and needed more personnel. However, the Dutch eventually forced Aceh to surrender by implementing a strategy to capture the Sultan’s wife, Pocut Murong. Due to the pressures, in January 1903, Sultan Muhammad Daud was forced to surrender to the Dutch. Several months later, due to the Dutch practice of capturing the wives of resistance leaders, Panglima Polim and Tuanku Raja Keumala surrendered. Since then, the rule of the Aceh Darussalam Sultanate, which had lasted for approximately 400 years, came to an end. However, the Sultan secretly continued to communicate with the resistance fighters in the hinterland and with Japan. The Dutch eventually knew about this communication, and the Sultan was exiled to Ambon. With this exile, the war between the Dutch and Aceh came to an end.

The Aceh War was the most expensive war in history. In terms of casualties, approximately 12,000 to 13,000 Dutch and indigenous soldiers were killed in battle. The Acehnese lost between 60,000 and 70,000 people. Even during the most peaceful period of Dutch occupation in the 1930s, the Dutch Governor warned that every Acehnese person buried a “fanatical love of freedom, reinforced by a powerful sense of race, with the consequent contempt for foreigners and hatred for the infidel intruder.” No one should underestimate the readiness of the Acehnese to sacrifice themselves for national pride.

Although the Acehnese rebels welcomed the Japanese, in 1944, a brutal uprising against the Japanese military broke out, becoming one of the bloodiest revolts in Indonesia. An uprising against Jakarta’s control under Teungku Daud Beureu’eh (who became the most influential cleric and revolutionary leader from 1945–1950) occurred between 1953 and 1962, and Hasan Tiro led another in 1976. The idea of an independent Aceh was never far from the minds of those opposing Jakarta’s status quo in Aceh. In 1953, Daud Beureu’eh led an uprising against Jakarta not for an independent Aceh but for an Indonesian Islamic State, which he believed Aceh fought for during the revolution.

References:

Ahmad, Z., Sufi, R., Ibrahim, M. & Sulaiman, N. (1982). Sejarah perlawanan terhadap imperialisme dan kolomialisme di Daerah Istimewa Aceh. Jakarta: Direktorat Sejarah dan Nilai Tradisional.

Reid, A. (2004). War, peace and the burden of history in Aceh. Asian Ethnicity, 5(3), 301-314, DOI: 10.1080/1463136042000259761.

Sudirman. (2012). Peutjoet: Membuka tabir kepahlawanan rakyat Aceh. Banda Aceh: Balai Pelestarian Sejarah dan Nilai Tradisional.